The Shejaiya district in the eastern part of Gaza City, where recently ten soldiers and officers of the IDF lost their lives, has always been considered one of the most dangerous and challenging areas for military operations in the northern part of the sector. The military usually attributes this to the density of buildings and the professionalism of Hamas's Shejaiya unit. It was in this area that the IDF suffered significant losses in 2014 during Operation Protective Edge. On Friday, December 15, the IDF spokesperson announced the destruction of the Hamas' Shejaiya' battalion headquarters; however, fighting with terrorists in this area is still ongoing.

One of the Israel Defense Forces units involved in the battles in Shejaiya is the 17th Battalion of the Bislamach Brigade's 17th Battalion (the Golani Lions Battalion). During peacetime, the 17th Battalion conducts courses for infantry commanders. During the first ten days of the war, the fighters of the 17th Battalion captured and eliminated terrorists who infiltrated Israel in the Zikim area. After that, the Battalion was transferred to Gaza, where it guarded humanitarian corridors and fought in battles in Jabalia.

The Battalion has been fighting in Gaza for a month and a half. During this time, the Lions only went home for a day only once.

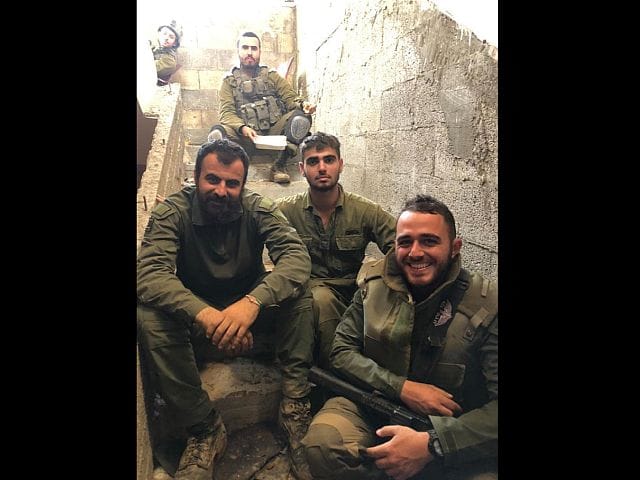

Alla Gavrilova spent several hours with the Lions of the 17th Battalion in Shejaiya.

Every day or every few days, the Battalion changes its positions. While heavy fighting occurs, the soldiers mostly sleep in APCs. The 17th Battalion primarily uses Achzarits - heavily armored personnel carriers based on Soviet tanks. Soldiers claim that 12 people can fit in one Achzarit. Commanders say that soldiers exaggerate, but not by much.

I am talking to the Lions in one of the surviving houses in this area, where the fighters of the 17th Battalion stayed overnight today. There are few such houses; most buildings are partially or entirely destroyed. There are no civilians in Shejaiya now. In some points of this area, there are battles, Israeli artillery is working, and smoke plumes from explosions are visible.

Instead of windows in partially destroyed houses, there are holes, and some windows are covered with blankets. I see a very cheerful children's picture - Sponge Bob Square Pants. Here and there, clotheslines and even laundry itself have survived.

Some fighters are on duty at the trenches, while others are resting. Some are sleeping right in the middle of the room, and others are making coffee. A correspondent from The Times of Israel is with me, and the Lions eagerly bombard us with questions about what's happening behind the lines – they don't always get to hear the news. One of the soldiers admits that a week before his furlough (the only one during the entire war), his close friend from another brigade was killed. My interviewee learned about his friend's death only after leaving Gaza.

"Well, luckily, my fiancée told me about it right away. I would have gone crazy if I found out on the way from the news. I mean, not a fiancée, but a girlfriend. I still need to propose. I'll do it as soon as we finish here..."

They offer me a Coke or a Sprite. They found several crates of cans near the house. The fighters say that boxes with humanitarian aid are often found in homes where terrorists hide.

I interview Senior Lieutenant Sharon Gutman, the military doctor of the 17th Battalion. Sharon, 28, made aliyah from Argentina when she was seven. She is from Beersheba and is currently serving in the army as she took a break from her studies to become a doctor. Sharon's husband, Yuval, whom she met at university, is a military doctor in the 51st Battalion of the Golani brigade.

How did the war start for you?

I was on furlough that weekend, so I went to spend Saturday with Yuval at the Kissufim base. Our free weekends often didn't coincide, so we used to go to each other's bases. So, I was there as his wife. Early Saturday morning, before six o'clock, and I was sleeping, Yuval went on patrol. I woke up to explosions. I put on sandals and glasses and ran out into the corridor in my pajamas. When I ran out, I realized I didn't even know where to run, but soldiers noticed me and dragged me into a protected room, which turned out to be the command post. And on the screens, I immediately saw terrorists running towards us. Several dozen soldiers in underwear or pajamas rushed into the command post. I didn't know where Yuval was. I saw him then when he, along with two paramedics, ran into the room, carrying wounded.

We started working. Two doctors, one of them in pajamas, several paramedics, one medical kit. The number of wounded kept increasing, so we divided the room into two parts – the light and the severe cases. I only saw injured in front of me and didn't even pay attention to the gunfire behind the walls. Sometimes, the lights went out, and we worked in the dark. They evacuated us from there late in the evening. In total, we assisted 22 wounded, as we were later told. We lost one man.

My husband and I indeed became doctors at that moment. It was a baptism by fire.

Have you assisted the wounded under fire for the first time?

Yes. I returned to the army in April 2022 and underwent a three-month military medicine course. I had been in my position for a year and three months, but I hadn't been in a situation like October 7. Neither had Yuval.

What was it like working together?

Channel 13 made a report about us and called it 'Love Under Fire.' There was no talk of love during those hours, but we worked seamlessly. Since then, I've seen him only once – we met at the border before each of our battalions entered Gaza. We spent only a few hours together. I had a one-day furlough, but not at the same time as Yuval.

What happened after Kissufim?

They brought me to Soroka Medical Center, where my parents had arrived. I took a shower, rested, and went to the battalion base where everyone was gathering. From there, the Battalion went to the Zikim area. Two weeks there, then – Gaza.

What does your work look like here?

In the Battalion, there are two doctors and several paramedics. Soldiers call us 'golden eggs' because they try to protect us as much as possible so that we can treat and evacuate the wounded. It is believed that the best way to save a wounded person is to get them to the hospital as soon as possible. So we assist the wounded right in the vehicles on the way to the border, where we hand them over to ambulances or get them on helicopters. We transport them either on Achzarits or Humvees if the situation allows. There have been several severe cases. The first severely wounded was our platoon leader; we evacuated him in critical condition. Last week, I finally had a furlough and went to check on him at Ichilov Hospital. He's okay, he's rehabilitating. It was the best moment for me during all this time.

Have you provided first aid to civilians?

Yes, twice. Once, when we were guarding the evacuation corridor. There were many children and elderly people who needed medical assistance. They have no medications; many are seriously ill. Of course, I'm a military doctor, and I don't have blood pressure medications, for example, in my first aid kit, but I gave them what I had. Not all of them wanted to talk to us, but they didn't refuse help. We tried to help everyone; we were trained for that, we took an oath. The second case was in a school from which we evacuated hundreds of people who were locked there by terrorists. There were not only sick people but there also wounded.

Did you have to assist terrorists?

No.

How many women are there in the Battalion?

Currently, both battalion doctors are women. Until recently, I was the only woman in the Battalion. It doesn't bother me at all. The guys understand some of my needs, support me, and help with medical equipment and stretchers. I'm pretty short, weigh 49 kilograms, and I have to carry half my weight on myself. But other than that, I don't see any difference; they respect me a lot. We work together with everyone. I even have advantages – they listen to me when I make them tidy up and maintain hygiene; we don't need more diseases. And if I need to change or wash, they respect my personal space.

Yesterday, for the first time in six days, I could wash my hair, and one of our soldiers poured water on my head.

You know, I look at you in all that military gear, and still, I see a typical girl next door and a quiet high achiever. How do you feel about yourself?

I was a quiet high achiever and a homebody until I was 28. Becoming a doctor was my childhood dream, but surely, I never thought I would become a doctor in Gaza. I can't even say that the war changed me, but I can say that it taught me a lot and forced me to mature significantly. And I discovered a lot about myself. I didn't know I had so much strength. I didn't think I could endure such hardships. I realized that to do well in my job in combat, you don't need to be a muscular athlete. All my female classmates are on the front line now, all fantastic women doing their jobs, and no one thinks we are less than men — neither we nor the men we serve alongside.

Photo: Alla Gavrilova. "The News Of Israel"

Do you already know what you want to do in civilian life?

Yes, I want to become a family doctor. But that won't happen anytime soon.

After the conversation with Sharon, I continue talking to the fighters. I asked the very young conscripts how they felt about having a woman as a doctor in a battalion consisting only of men. Several admit that they were initially uncomfortable, considering the field conditions. Still, they quickly got used to it, and creating personal space for Sharon became a habit they no longer noticed.

I ask the guys about contacts with the civilian population during the humanitarian corridor protection, and I get an unexpectedly detailed answer.

"You constantly experience conflicting feelings. On the one hand, you feel sorry for them—elderly people, women, children, many barefoot, asking for water. But you remember October 7; it doesn't leave your mind, and you immediately think that this kid probably wants to kill you. Maybe this woman's son called her from Beersheba and bragged about the number of Israelis he had killed. But you can't refuse to give them water. Why not? Look at this room. Do you see that we covered all the windows with sheets and blankets? Do you understand that we entered the house, opened the closets, took out the belongings of the people who lived here, and we use them, we trample on them? Personally, I feel that I became a bit of a beast at that moment. You can easily become a beast here. And when we gave water to these people, I felt like I was doing it for myself."