Natalia Casarotti, mother of Keshet Casarotti, who was killed in the Nova music festival massacre, honors her son's memory through various projects and actively shares her story to ensure the victims are remembered while supporting other affected families.

Natalia Casarotti is a beautiful, incredibly talented, intelligent, and kind woman. She is one of those whom Israelis call "salt of the earth." She spent 30 years living in a small kibbutz called Samar in the Arava Desert, where she raised her three children. Now, the entire country knows her as "Keshet's mom" – the mother of the charming young boy Keshet Casarotti, whose face became familiar after the Nova Festival massacre on October 7, 2023. Many believed Keshet came from a Russian-speaking family, and his mother's name, Natalia, reinforced this assumption. However, the family has roots in South America.

Natalia Casarotti was born in 1973 in Argentina. During the dictatorship, her family first moved to Brazil and then to Israel. During the Six-Day War, her mother volunteered in Kibbutz Ginosar and decided that they would live in a kibbutz when she had a family. Initially, the newly immigrated family settled in Kibbutz Dan, but it was challenging: Kibbutz Dan practiced separate living arrangements for children and parents, with children sleeping in a communal nursery, which conflicted with the young family's needs. They moved to Karmiel, where Natalia grew up and was drafted into the army.

Natalia served in "Gar'in Nahal" in Kibbutz Ga'aton near Ma'alot, and after her service, she moved to the Arava Desert, where she built her future. "I read an ad in the kibbutz newspaper about an opening for a kindergarten teacher in a small kibbutz, Samar. I had loved desert trips since school. So, the desert, the small kibbutz Samar, where I worked for six months, then went to South America after my discharge to meet relatives." After returning from this trip, Natalia visited friends in Kibbutz Samar with a small weekend bag – and ended up staying there permanently.

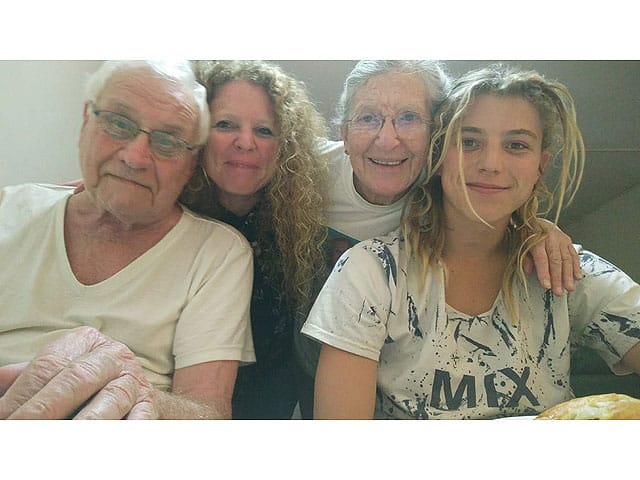

Thirty years have passed since then. In Kibbutz Samar, Natalia Casarotti became the mother of three wonderful children: her eldest daughter Anan (meaning "cloud"), her son Keshet (meaning "rainbow"), and her youngest daughter Shemesh (meaning "sun"). Her eldest daughter is 24 years old and recently completed her service in the Air Force; her youngest daughter, 18-year-old Shemesh, decided to serve in Sherut Leumi. Natalia Casarotti's only son, Keshet, will forever remain 21: on October 7, he was killed by Palestinian terrorists at the Nova Festival.

Keshet was a real man

According to his mother, Keshet was very natural and authentic. Whether in the August heat or the winter cold, he would walk barefoot, wearing just shorts and a T-shirt. "I would ask him to dress warmer and put on shoes, but he would explain that he wasn't too hot or too cold; he always felt comfortable," Natalia recalls. "When it rained – and in our desert, rain immediately creates puddles and even floods – Keshet would jump into the puddles in his clothes and shoes early in the morning. He loved playing in the water and was very happy in those moments."

Keshet was very kind and responsive, always helping everyone, whether carrying something heavy or collecting trash and branches in the neighbors' yards. He was very flexible and artistic; at age five, he started walking on his hands and would walk on his hands from home to the kibbutz dining hall. He was very musical, singing many songs – not just children's songs but also Israeli pop classics, without missing a note or mixing up the lyrics. As a child, Keshet loved pirates and everything related to them: adventures, treasures, coins.

School was challenging for him: not every teacher is ready to accept a child who doesn't fit into standard frameworks, and Keshet was never "standard." Problems with teachers began in the first grade, and his mother had to navigate, giving her son as much freedom as possible while ensuring he met the teachers' requirements.

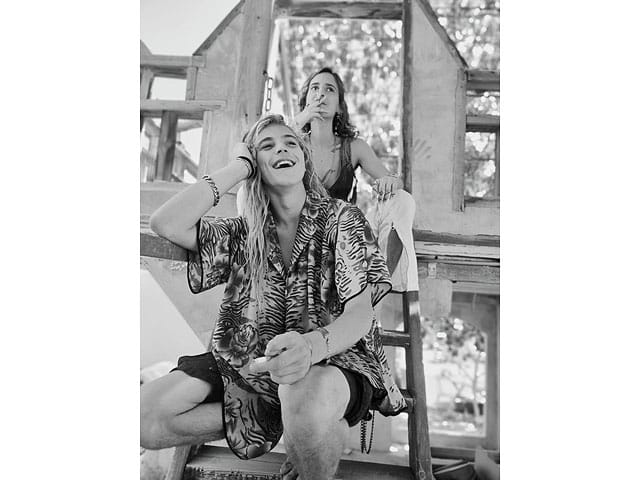

Keshet completed his last twelfth grade ("Yud-Bet") in a "small" class with a more individualized approach. He then began working on the "Ashram in the Desert" project, through which he met many wonderful, like-minded people. This experience introduced him to the festival life and, in essence, led him to a new family of kindred spirits. Keshet lived and socialized in Tel Aviv's legendary Florentin neighborhood, in communities around Mount Carmel and Jerusalem, and traveled to various festivals, mainly in Europe – festivals became his true passion. Like many young people in this circle, Keshet took jobs to save money for the next festival, living from festival to festival.

"He was only 21, so I didn't expect Keshet to have a clear idea of what he wanted to do," admits Natalia Casarotti. "On the contrary, I really like living day by day because later we have so many years of seriousness, responsibility, and monotony. However, people who met him at festivals over the past year told me that in conversations, he expressed a desire to settle down, put down roots, meet a girl, have children, and start a family."

The 21-year-old Keshet traveled extensively, rarely living at home with his mother. He socialized with friends, met new people, and enjoyed life. "It turned out that over these past eight and a half months, I learned so much more about him because many people have shared their stories with me," Natalia Casarotti shares. "They tell me about their adventures, experiences, and memorable moments with him. Yesterday, a girl who didn't even know him or me wrote to say she dreamed about him. I've encountered several people like her. It's so touching that people find ways to tell me about their dreams and memories of him. Some just saw him for a few seconds on the street and haven't forgotten. Others met him dancing at festivals, in the synagogue, or at a celebration. Even these brief encounters left an impact, and people share these stories with me, helping me learn more and more about my son. Keshet wouldn't have told me such things himself."

One reason this fair-haired, tanned young man left such a lasting impression on so many people is undoubtedly his appearance. "You've seen it yourself; Keshet was incredibly handsome. And I know it wasn't easy for him," admits Natalia. "He wanted people to see more than just his looks. He didn't want to be judged – positively or negatively, it doesn't matter – solely on his beauty. He was very modest. He wanted to be known and valued for who he was, for what was inside, and he wanted to achieve his place in life because of his qualities and character, not because of how he looked."

Keshet's mother shares that he was deeply empathetic towards people – without exception. It was important to him that any homeless person at the central bus station received humane treatment. He would buy them food, help them with money, and talk to them. "He would ask how they were – those very people whom no one notices, who are invisible to the crowd. I think this meant a lot to them," Natalia acknowledges. "Keshet was a real man."

Bnei David Synagogue, Florentin, Tel Aviv

In the last two years, Keshet Casarotti became an integral part of the Bnei David Synagogue community in the bohemian Florentin neighborhood of Tel Aviv. Within this community, mutual communication, support, and cooperation are highly valued, and through these connections, Keshet grew closer to religion. He spent Rosh Hashanah at a festival in Greece, and it was very important for him to observe Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, according to tradition alongside other Israelis. Among his friends were Shani Louk and her boyfriend Orion Hernandez, whose faces are also painfully well-known to every Israeli: Shani and Orion were also killed by terrorists at the Nova Festival.

"It was important for Keshet to go to the Beit Chabad, start the Yom Kippur fast on time, and put on tefillin," Natalia recounts. "At festivals he attended over the past year, even if bands he was looking forward to were performing on Friday, he would set it all aside. It was important for him to arrange a Shabbat meal and greet Shabbat with his friends. At these festivals, he only ate kosher food, which is not easy in the tented festival camps in Europe. This was his intention, his desire, and his choice."

Therefore, Keshet's family had no hesitation when deciding how to conduct his funeral. Samar is a kibbutz founded by the left-wing socialist Zionist movement Hashomer Hatzair, where religious traditions are uncommon. Natalia Casarotti herself leads a secular lifestyle, and the kibbutz is entirely secular, with no prior religious funerals conducted there according to Jewish rites.

"My son was buried according to halachic Jewish traditions," Natalia notes. "But it was much more than that: there was a spot in the middle of the desert, and there was music – Shlomo Artzi, Zohar Argov, and the Brazilian singer Roberto Carlos, whose songs have been with us since childhood. It was that kind of day."

Some time ago, Natalia Casarotti learned about a new organization that searches for and restores damaged Torah scrolls and returns them to use. She was inspired by the idea of bringing a Torah scroll from Brazil – a country significant to both Keshet and herself – restoring it, certifying it according to all Jewish laws, and ceremoniously bringing it into the Bnei David Synagogue for the next Simchat Torah holiday. The wood and materials used for restoring the Torah scroll will come from the settlements of the Gaza Envelope, which were burned on the day her son died, giving the Torah new life. "This seemed ideologically very close to us, Keshet, and the Florentin synagogue where he spent so much time," Natalia notes. "There are synagogues that house dozens of Torah scrolls, but this organization aims to help small, remote synagogues that have to borrow a Torah scroll."

Keshet Casarotti, who was killed by Palestinian terrorists on Simchat Torah and for whom religion and the Bnei David Synagogue had come to mean so much, would likely have appreciated such a gift. Natalia is currently working on this project.

Life after October 7

For 20 years, Natalia Casarotti fed the entire kibbutz. She loves cooking and holds a chef's diploma. The kibbutz used to have a small Italian restaurant run by Natalia. "After October 7, I simply don't feel like cooking," she admits. "This has never happened to me before. Sometimes, I cook for my daughters; after all, the home should still feel like a home, and a mother should still be a mother."

Her main goal now is to ensure that the massacre on October 7 is not forgotten, that the crimes of Hamas are remembered, and that the innocent victims are not forgotten. She wants the world to remember our hostages. "Two days after it had been 30 days since Keshet's death, Shemesh and I went to Mexico as part of an Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs delegation," Natalia Casarotti shares. "There were press conferences, journalists, and representatives of Jewish communities. Since then, it's been important for me to speak about them and write about them—about my son, but not just him. About those who died. And who would have thought that it would still be relevant—to talk and write about kidnapped Israelis? How naive we all were, expecting them to return soon..."

Natalia finds new channels for this activity: she writes on social media, sharing her life story. "I started learning the art of DJing," she confesses. "My dream is to play music anywhere in the world, and I know that wherever I play, my son's light will shine, and his memory will be there. It's another way to connect with him and to connect others with him. Music transcends boundaries, age, and religion; it goes beyond all that. This is becoming an important part of my life now."

About two or three months ago, Natalia Casarotti realized that we are left with memories and photographs of those who have passed. "Almost every day, I come across a photo I had forgotten or missed," she shares. "People send me photos. These photos capture moments, making them eternal. I used to take pictures before, but now I'm getting more serious about it. I want to photograph families in our beautiful desert here, among the dunes. I want to give people those moments of unity with themselves and the desert. I want to photograph people well past 20 because we forget that we can be beautiful; we stop believing in ourselves. I want to remind people of this, to photograph them in a safe and peaceful place here in the desert."

Music, recording, and photography have allowed Natalia Casarotti to continue living and helping others. "Every day, I have to make a choice," she says. "I have to choose to get out of bed. I have to choose to keep living. I have to choose to take action. I want to have a voice. Now, my voice is much stronger. Some people find it hard to speak up—they have no voice. And I know that my voice is for them, too. We live near Eilat, and I'm now fighting for a basic thing—a support group for families like ours. Five other families in Eilat lost loved ones at the Nova Festival and people who lost soldiers. It's important for us to sit together, talk, and share. And what about the rights of the siblings of the deceased? For their grandparents? My 85-year-old father buried his grandson. All this is very hard for me. Most of the time, I am strong, but this breaks me. Despite this, I have the ability and strength to do this. I have to do it because no one else will. No one else will secure a support group; no one else will support the grandparents. Yes, the situation is difficult, but let's think about how we will continue to live in it."

"Shemesh finished 12th grade," Natalia continues. "And I suddenly think about how proud Keshet would be of her. It's a pity he's not with us. Her birthday is soon, and now there are so few of us—just me and my girls. But life continues; there will be happiness again, the girls will find their love, grandchildren will be born, and life will continue. There will be many good things, and I look forward to them. But how long will I live with this pain? I'm 50; maybe I'll live to 90. So40 years with this pain? And my daughters will live with it for 80 years? Because he is with us everywhere, every minute."

Natalia Casarotti admits that speaking to the journalists and giving interviews is difficult for her. "Sometimes you feel like you didn't tell everything, that your story just filled a five-minute gap in a radio host's program," she says. "And now the price I pay—as everyone knows who my son was, people start recognizing me. The most sacred thing in my life was my anonymity; I didn't want to be recognized on the streets; my private life was sacred to me. I didn't seek out television. But now, I have a title—that title is 'Keshet's mom.' It comes with great responsibility. Great meaning. A great duty. And although I pay a high price for this title, I accept it."

Over Keshet Casarotti's grave stands a semicircular monument carved from sunset-colored desert stone. It reads: "Keshet, son of Natalia."